WILD BOAR

Wild boar Sus scrofa

Taxonomy

Class : Mammals

Order : Artiodactyla

Suborder : Nonruminants

Family : Suidae

Genus : Pigs (Sus)

Species: Wild boar (Sus scrofa)

Distribution

The Distribution of the wild boar extends on large areas of Europe and Asia. Very dry areas and areas affected by groundfrost over a longer period of time are not colonised. In Switzerland, the Wild Boar populates the Low Lands, the Jurassic Mountains, parts of Ticino and the Rhone valley. The colonisation of the Low Lands and Prealps has not yet been completed. Anthropogenic barriers, especially Motorways, restrict the distribution of the Wild Boar.

Habitat

Basically, the wild boar is a typical forest animal. However, due to its high adaptability it is also present in other habitat types e.g. wetlands or in the Mediterranean region of Macchie, as well as in cork and holm oak plantations. Farmland is visited for food intake and if the vegetation is dense and higher than 70 cm, agricultural land is often used as hiding place. In recent times the new phenomena of the so called urban wild boar was observable in cities such as Barcelona, Berlin and Katowice, where several thousand wild boar live in and around the city, like the foxes. In Switzerland wild boar migrate to an altitude of up to 2000 m in wintertime and in the mountains of central Asia even up to 4000 m.

Anatomy

Viewed form the side, wild boar seem to be bulky and clumsy, however, if observed from the front, they have a slender appearance. The triangular head, the short and massive neck and the short robust legs are further characteristics of wild boar. With their typical body shape, like a wedge, wild boar can move agilely through thick undergrowth. The wild boar’s distinguished look comes from its pelage, consisting of a dense under coat and longer guard hair. The under coat particularly serves for thermoregulation and covers the entire body except some parts of the head and lower limbs. Besides thermoregulation the pelage protects the wild boar from injuries, parasites, sun or rain and serves as camouflage. In spring the wild boar loses its long and dense winter hair and changes its coat into a short and under wool free summer fur. The change of coat takes place during a period of about three months and starts in Central Europe in the months April through May. During the first three to four months the piglets have a typical camouflage coat. In the undergrowth’s interplay of light and shadow the piglet’s light brown stripe pattern perfectly blends in with the surroundings.

Perception of the Environment

Olfactory sense: for wild boar the olfactory sense is important for foraging, communication and the detection of enemies. The olfactory organ of wild boar is highly developed, the size of the olfactory cells and the density of receptors even exceed those of dogs. Under favourable wind conditions wild boar are able to smell an enemy over a distance of up to 500 m. Moreover, wild boar can smell hidden food underground like insect larvae, nests of mice and roots. Even with a snow layer of 30 cm they can still find food with their excellent olfactory sense. If two adult wild boar happen to meet, they make nose contact immediately in order to identify each other. Also, the recognition between mother and child happens through smell when making nose contact. The piglets recognize their mother by the smell coming from the carpal gland located on the front legs of the wild sow.

Auditory sense: wild boar have excellent hearing. The auditory sense plays an important role not only for detection of enemies, but also for communication. Wild boar can recognise individuals by the means of their voice. With their fine hearing they are also able to locate mice.

Sense of sight: compared to humans, the eyes of wild boar contain more rods (important for light/dark vision) and fewer cones (important for colour vision). Consequently, wild boar have better sight at twilight but can’t distinguish colours as well as humans. The wild boar’s eye does not have a tapetum lucidum (residual light amplifier) as it is the case for other wildlife (roe deer, red deer, lynx and wolf). This could be an indication that, through evolution, wild boar are adapted to be active during daytime. However, it is also possible that for wild boar the ability to see in the dark plays a minor role as information on the environment that is essential for survival, e. g. the recognition of danger, is perceived with the olfactory and auditory senses.

Tactile sense: The wild boar’s trunk with its many short tactile hair, also called litter, is a particularly sensitive tactile organ. The lower lip and the tongue are also important tactile organs which allow the wild boar to find single grains and insect larvae from the ground.

Gustatory sense: wild boar have a well-developed gustatory sense, which enables them to avoid poisonous plants and distinguish different potato varieties. Wild boar have a preference for starchy potato varieties.

Food

Wild boar spend most of their time looking for food and can cover distances of up to 10 km per night. Wild boar are omnivores, consuming both plant and animal based food. The diet depends strongly on the available food supply and varies greatly between different habitat types and change of seasons. Early in the year (starting as early as February) the lesser celandine (Ranunculus ficaria) benefits from the available light reaching the forest floor. Before trees start producing leaves and thus intercept a large portion of sunlight with their foliage, the lesser celandine grows and stores already energy into its tubers. From the end of March to the beginning of May large areas are then covered with the lush, dark green leaves and the yellow blossoms of lesser celandine. Wild boar are really keen on the nutrient-rich clubbed and thickened tubers of the lesser celandine. The small nutritious breeding tubers located in the lesser celandine’s leaf axils are also widely consumed by wild boar. In Central Europe, acorns and beechnuts are an important part of a wild boar’s nutrition. In so called mast years (years when oak and beech trees produce particularly high amounts of fruits) wild boar benefit strongly from this food supply. Consequently, the population can increase greatly as also weaker individuals can survive the shortage of food during wintertime. On agricultural land the table is abundantly set for wild boar. They benefit from corn and grain cultivation and like to look for earthworms, beetle larvae and other invertebrates in meadows, pastures and fields.

Social Structure

Wild boar live sociably in sounders and show a highly developed social behaviour. There is a hierarchy within the sounder that is graded according to age and body size. The leading wild sow, an old and experienced female, is the leader of the sounder and defines where and when foraging and resting takes place. The leading wild sow determines also the timing for reproduction whereby the other females’ reproduction cycles synchronise with hers.

Mother families: basic structure, wild sow with piglets

Family group: Consist of leading wild sow and several adult wild sows with their daughters and piglets

Group of youngsters: several subadult wild boar

Solitary males: from the second to fourth year on male wild boar live solitarily

Rut time harems: during rut adult male wild boars join mother families or family groups

Reproduction

Wild boar reach sexual maturity at an age of nine to eighteen months. The point of time for active reproduction, however, depends on the respective living conditions. Rutting season lasts from November until February. After a gestation of three months, three weeks and three days, four to six piglets are born. The piglets are born with hair and open eyes and are after a short period of time quite mobile. Suckling lasts two to three months and piglets can already consume solid food from the second week on.

Ecological impact

From spring until autumn wild boar are rooting around 120 m2 of forest and grassland per day. This is equal to a surface area of about four soccer fields per year. Wild boar consume large amounts of insect larvae, mice as well as seeds and roots. Soil aeration, water balance and mixing of humus with lower soil levels are improved by rooting. The natural rejuvenation of the forest is promoted by wild boar as vegetation that prevents rejuvenation, like grass and bracken fern, is removed. In wetlands new growing sites for orchids and sundew are created as raw soil is exposed due to the rooting activities. Wild boar remove carrion and feed on young rabbits, fawns and clutches of ground-nesting birds. Wild boar also contribute to the dispersal of seeds and fungi e. g. of the truffle.

Signs of wild boar

A face to face encounter with wild boar is a thing that one rarely has the opportunity to see. However, field signs often reveal their presence.

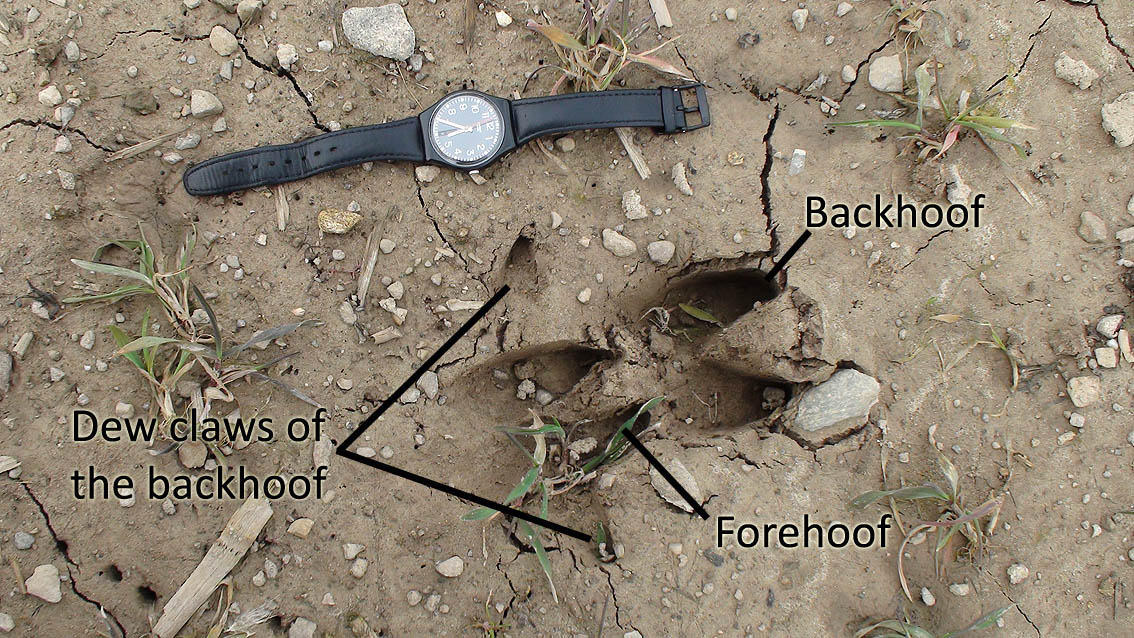

Tracks: Typical for wild boar tracks are the crescent-shaped imprints of the two dew claws laterally behind the hoof prints.

Trails of wild boar: trails regularly used by wild boar are easily recognisable.

Mud-wallows: wild boar love mud-wallows. Except in the deep of winter, mud-wallows are visited year-round, most frequently in summer. The mud-baths serve as thermoregulation and protection against and removal of parasites.

The rub trees: close to mud-wallows so called rub trees can often be found. Rub trees can be readily identified as the bark is partly scraped off and the trunk is coated with dried mud. These are signs that wild boar have rubbed against the tree.

The resting site: the resting site is a kind of nest, which is built in a well-hidden, dry and wind-protected spot. The resting site serves as sleeping place and hideaway for new-born piglets. These hideaways are changed frequently.